EVP and COO Rachael Nava appoints new Systemwide Vice President for Human Resources

January 14, 2026

Rachael Nava, UC Office of the President executive vice president and chief operating officer, shared the message below with the UCOP community on Wednesday, Jan. …

President Milliken to speak at the Commonwealth Club World Affairs of California

January 14, 2026

President Milliken will discuss the future of higher education, public research investment and how universities drive innovation.

My UC Retirement: Your source for “All Things Retirement”

January 14, 2026

Planning for retirement can feel overwhelming—especially when you’re juggling today’s needs with long-term goals. My UC Retirement is designed to make retirement planning easier by …

UC Spotlight: 5 staff stories that inspired us this month

January 14, 2026

Our monthly UC Spotlight article celebrates UC staff and teams who are making a difference for Californians and the world beyond our state.

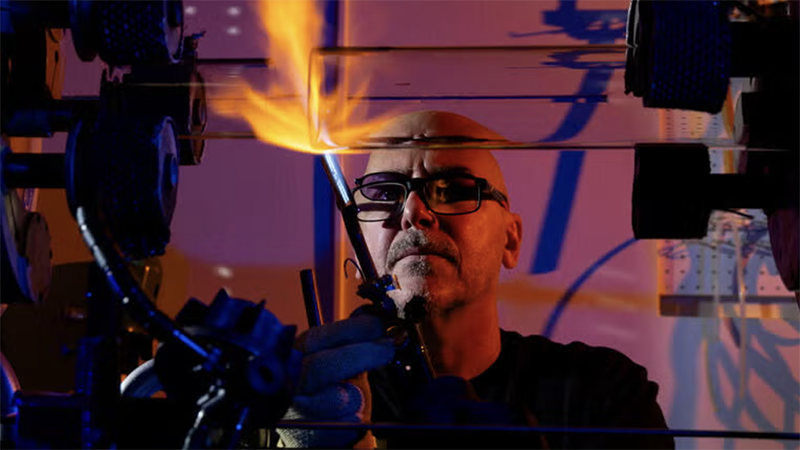

UC People: Stephen Lepore, scientific glassblower

January 13, 2026

Stephen Lepore quietly supports university research by creating and repairing the custom glassware modern science demands.

Systemwide webinar: Document Once, Improve Continuously

January 13, 2026

As teams evolve and reorganize, clear process documentation is essential. On Jan. 30, from 10 – 11 a.m., join UC Systemwide Procurement for an informational …

ICYMI: Subscribe to President Milliken’s Substack

January 13, 2026

Subscribe to get information and updates about the University of California from President Milliken’s point of view.

NRS leader Steve Monfort featured in California science panel

January 12, 2026

A state research event spotlighted how the UC Natural Reserve System is shaping biodiversity monitoring and climate forecasting statewide.

UC statement on Gov. Newsom’s 2026–27 state budget proposal

January 9, 2026

President Milliken is deeply grateful to Governor Newsom and California legislative leaders for their ongoing support of the University of California.

Systemwide event on Feb. 4: Learn how strategic planning works at UC

January 5, 2026

On Feb. 4, attend a special virtual event focused on how strategy can guide UC teams and locations, especially in uncertain times.